SPOILER ALERT! If you haven’t watched season 6, episode 1 of Black Mirror – stop reading now. Watch it (we get it, you’re cool for not watching what everyone’s talking about) and come back to this article.

Jump into the privacy pandemonium of Black Mirror Season 6, where consent, employee rights, and Salma Hayek dance a complicated tango.

Was I hooked? Definitely.

Did Krish spark a culinary revolt among spice-loving Indians? Indeed.

Did it conquer the privacy law maze? Not by a long shot.

Enter Joan, who discovers a Streamberry series that’s essentially a carbon copy of her life. From her texts to therapy sessions, to even confidential company information - nothing is off limits. What’s the fallout? A love life in ruins, a job down the drain, and a tarnished reputation.

In the legal world, these are 'actual damages'. Joan's got a laundry list of them and understandably seeks legal counsel.

Cue the collective groan from privacy professionals worldwide as Joan gets the textbook ‘I’m sorry, there’s nothing you can do’ spiel. Supposedly, Streamberry's fine print – which she agreed to – gives them an all-access pass to her life via her phone's mic and camera.

Without further ado, let's delve into the privacy faux pas in this Black Mirror escapade. Let's dissect, analyze, and in true Black Mirror fashion, probably leave you questioning everything you thought you knew about privacy rights. Buckle up.

Transparency and privacy notices

The lawyer claims that because Streamberry’s terms and conditions give them the right to all of your data, absolutely nothing can be done to poke holes in this from a legal standpoint. This could not be more false.

First off: this blatant invasion of privacy would set off alarm bells in any human rights court. Consumer protection laws across the globe explicitly state that you cannot sign away your basic human rights through a contract. If Streamberry mentioned in their T&Cs that you had to participate in a series of deadly challenges where survival guarentees a huge cash prize (Squid Game anybody?), and you knowingly or unknowingly sign it — it is still not binding or legal. And while challenges to the death certainly trump data misuse in the outrageous stakes, both scenarios violate basic human rights, and therefore, are illegal. Period.

The very first thing that the lawyer should have done was submit a complaint to a privacy regulator, consumer protection regulator, or Attorney General in the area.

In fact, privacy regulations today specifically state that companies need to have clear, conspicuous privacy notices in place that are easily accessible to customers and state what data is being used and how it is being processed. The whole point of these notices is to ensure that organizations are transparent with their customers about their data processing methods. Even if Streamberry were to argue that their T&Cs serve as a privacy notice and were accessible for anyone to read on their website (we’re giving them the benefit of the doubt here) — it still wouldn’t be compliant with any major privacy regulation as the privacy implications need to be mentioned much higher up in their communications.

In other words, burying a clause as important as, “all your data can be used by us and made public via a tv show”, in your T&Cs is not going to cut it, and would not hold up in any court as compliant with privacy regulations. Not only that, but transparency notices also require so much more than one clause. Companies need to clearly explain the following to their customers:

- Categories of personal information collected/used

- Purposes for collection/use

- Companies need to be very specific here

- If they claim that data is being used for a certain purpose, it cannot be used for any other purpose unless specified

- Where this personal information is collected, i.e., the source

- Categories of information shared with third parties

- Categories of third parties that data is shared with

- How customers can access their rights, which include:

- Right to data deletion

- Right to restrict processing

- Right to withdraw consent

Joan was denied access to all of these rights, and her lawyer appeared to be blissfully unaware of them. I’m starting to think the lawyer was on Streamberry’s payroll.

How customers can appeal a decision related to a rights request

Even if Joan was able to request her data be deleted and Streamberry denied it, they’re still required by law to explain why they made this decision. In some cases, a regulator would need to agree with Streamberry’s decision in the case of an appeal.

Contact details of the business and/or data protection officer (DPO)

Considering the absolute privacy mess that is Streamberry, there’s a good chance they don’t employ a DPO (or they have one who’s completely mailing it in).

This is all to say — Joan, for the love of Max Schrems, please get a new lawyer.

User consent

Another blatant privacy fail in the episode is the matter of Joan’s consent. While Streamberry tried to get out of this by stating that the contract with the streaming service was the legal basis to process this data, we’ve gone over how this has no validity under any regulation out there today. While consent would have been their best bet for any hope of legal operation, there was a complete lack of effort on Streamberry’s part to gain valid consent to collect and process her data.

Nearly all major privacy regulations define consent based on the following aspects:

- Freely-given – Given by the users on a voluntary basis

- Specific – Users should know who the controller is, what data is processed, and how it will be used

- Informed – The user should be informed that they can withdraw consent at any time, and be shown the mechanism to withdraw their consent

- Unambiguous – Requires a clear, affirmative act

However, in the case of the GDPR, consent is only valid in an opt-in mechanism where users must opt-in to the processing of their data. In other major privacy regulations across the world, opt-out mechanisms are also valid, where users must opt-out of the processing of personal data. In either case, however, clear action must be taken.

So at the end of the day, what does all this mean for Joan? Let’s go down the list.

Was her consent freely given?

No. She never gave her consent, let alone freely (opt-in or opt-out), for her data to be processed this way.

Was her consent specific?

No again. She was never informed that her data would be used in this way.

Was her consent informed?

No, again (I’m starting to see a trend here …). She was never aware that her consent could be withdrawn (in fact, she never gave consent).

Was her consent unambiguous?

No. She never took a clear affirmative action to give her consent for this data to be used as such.

That gives us 4 solid nos across the board regarding how Streamberry handled user consent regarding personal data processing – meaning we have a wonderfully illegal use of data staring us in the face.

To quote Parks & Rec, “straight to jail”. Or in this case, probably a hefty fine.

Sensitive data

Another wrinkle in the show until now is that Joan’s therapy sessions are used by Streamberry without an extra layer of consent required to process this data. Therapy sessions fall under the bucket of “health-related data” which is considered sensitive data by every major privacy regulation in the world. Not only is it just the health data from her therapy session, but also the data concerning Joan’s sex life with the scenes of her and her ex that also fall under the category of “data regarding one’s sexual orientation”, which is another subcategory of sensitive data.

Companies are required to obtain an extra layer of consent in order to process this personal data. In fact, under the GDPR, the only legal basis for processing this data is “explicit consent”. This means that this type of consent needs to follow the points below:

- An explicit consent statement needs to specifically refer to the element of the processing that requires explicit consent

- Specify the nature of the special category data

- Details of the automated decision and its effects

- Details of the data to be transferred and the risks of the transfer

- The ‘explicit’ element of any consent should also be separate from any other consents you are seeking

Given that Streamberry failed to process the consent of even non-sensitive personal data accurately — in the case of sensitive data, they have failed magnificently. The use of sensitive data would also have to be called out explicitly in a privacy notice. So not only is there no legal basis for Streamberry to process this data, but they’ve also given no option for users to consent or even opt-out of this processing.

In the case of processing sensitive data such as health data, organizations are required to conduct risk assessments to identify any spots in the data lifecycle where their users’ privacy is compromised and ensure adequate data security provisions. In fact, these data protection impact assessments (DPIAs) are to be conducted from the point of view of individuals or data subjects. Ironically, the primarily rule of thumb in these assessments is “if the individual would be unpleasantly surprised if they understood what is being done with their data, it is a process that needs to be changed.” That statement alone sounds like a synopsis of the episode.

Even if we give Streamberry more benefit of the doubt (that they don’t deserve) and assume that they have state of the art data protection measures on the security side, including encryption, anonymization, and pseudonymization — there’s still the gaping hole of privacy compliance. The concept of Privacy by Design, which is a staple of nearly all major privacy regulations, states that companies need to include privacy as a key factor of consideration from the inception of any new product or service, not an afterthought. By the look of things, Streamberry executives have tried their best to introduce a new concept, “No Privacy by Design”.

In the words of DJ Khaled, “another one” (fine for privacy non-compliance that is).

Device permissions

The main crux of how Streamberry uses their viewers’ data is based on their devices keeping microphones, location, and cameras on, and then subsequently sharing this data with the streaming platform to use for their content.

You’ve probably heard your older relatives complaining about how “the phones are listening” and show them ads based on conversations they have. In the Streamberry-verse, they’re definitely right. While we all set device permissions on our phone for the location, microphone, and camera with different apps, they use them for specific and limited purposes defined by the respective apps.

In the case of sharing personal data with a streaming app, not only does this require additional consent and proper notices in place, but your device does not have the right to share this data with third parties without your knowledge and permission. This blatant disregard for basic privacy compliance shows off the Streamberry “No Privacy by Design” framework at its finest. Streamberry’s mode of data collection is, yet again, illegal.

They’ve got a real knack for disregarding user privacy at every turn. I can almost imagine Oprah reading Streamberry’s data policies — “You get a fine, you get a fine, you get a fine!”

First-party data

We talk a lot about the importance of collecting first-party data at OneTrust. Please don’t go about it the way Streamberry does though. Personalization is important – and every study has shown that personalized offerings and content increases customer engagement and brand loyalty. But it needs to be done the right way – honoring your user privacy and ensuring you’re transparent throughout.

Also, who wants to see a tv show about themselves (shout out to all my narcissist readers)? TV shows are generally about escaping your daily life for a short window – not reliving your life (especially the worst parts edited for maximum pain) again and again. More effective personalization would be to collect preferences via surveys, feedback, and viewing data to curate the best possible TV show collection for users – keeping them engaged and on the platform for the most possible time.

(Privacy) food for thought: Image licensing

The whole concept of Salma Hayek licensing her image to be used in the tv show is a primary factor in the plot. This raises many interesting questions around privacy regarding how this ‘digital twin’ is used. There’s a good chance you’ve seen a deepfake video of a celebrity saying something that they’ve never said in real life. Are deepfakes a violation of privacy for the person? Can deepfakes of the general public be used to create echo chambers and perpetuate bias? Does this technology have the ability to perpetuate harmful and/or inaccurate data? Does a public persona’s face count as biometric data and therefore fall under the bucket of sensitive data?

This brings up the line between publicly accessible personal data in the case of many celebrities vs. people's personal data in the public eye. When personal data is already willingly shared with the world via social media or otherwise, it’s generally considered fair game to use it without the same level of protections that people’s personal data is usually given. However, when someone’s personal data that has not been willingly shared with the public gets exposed, that’s when the matter of privacy compliance and breaches come into play.

With these new technologies surfacing, privacy laws are still evolving to meet our expanding digital reality. While licensing your image under a contractual agreement with T&Cs that define its use is completely legal, the involvement of AI leaves the possibility of an unknown outcome with how this image may be used. In this case, is it even fair to give consent or is the layer of AI added on to image licensing considered a violation of basic privacy rights?

The privacy implications of deepfakes and image licensing powered by AI are both factors that need to be addressed in the next wave of privacy regulations.

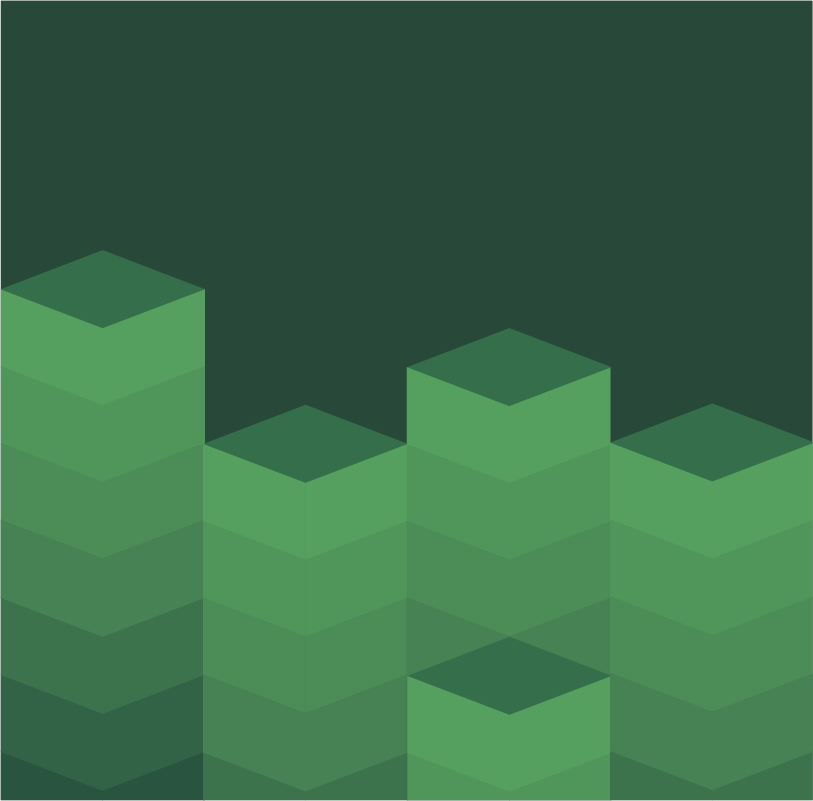

Where in the world is Streamberry illegal?

To really drive home how illegal this streaming platform is – here’s a table that shows where in the world Streamberry’s operations would be illegal today.

NOTE: These are just a few examples of countries where Streamberry’s operations are illegal, the comprehensive list would require another entire post of its own.

| Country/Region | Regulation | Enforcement Agency | Is it illegal? | What part of the law does it break? |

| California | CCPA | California Privacy Protection Agency (CPPA) | Yes | Privacy notice and disclosures, consent, sensitive data requirements |

| UK | UK GDPR | Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) | Yes | Privacy notice and disclosures, consent, sensitive data requirement |

| Europe | GDPR | Data Protection Authorities (DPAs) from 27 member states | Yes | Privacy notice and disclosures, consent, sensitive data requirements |

| Canada | Bill C-27 | Office of the Privacy Commissioner (OPC) | Yes | Privacy notice and disclosures, consent, sensitive data requirements |

| Brazil | LGPD | National Data Protection Authority (ANPD) | Yes | Privacy notice and disclosures, consent, sensitive data requirements |

| China | PIPL | Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) | Yes | Privacy notice and disclosures, consent, sensitive data requirements |

Then again – do any of these laws really apply in fictive layer 1?

For the latest in privacy, security, ethics, and ESG, keep up to date with the OneTrust blog.